The spectral figure of the little old lady in tennis shoes returns periodically to haunt animal rights activism and theory. It was Cleveland Amory, founder of the Fund for Animals (later folded into the Humane Society of the United States), who was known for saying “we aren’t little old ladies in tennis shoes” anymore. After the March for Animals in 1990, young male activists were quoted in the Washington Post proclaiming this same idea.

Let’s consider for a moment this back-handed compliment. One thing that is being said is “before the rest of us discovered the legitimate and important issues about human’s oppression of the other animals, little old ladies had.” Perhaps when they started agitating on behalf of animals they were not little old ladies. Recently, I noticed a thread discussing the author of The Sexual Politics of Meat that said, “well, she’s old.”

What’s “old” anyway? Some cultures might revere their eldest members as sages or crones, the wise old woman in archetypal and pagan terms. I love the tribute book to Jane Goodall (The Jane Effect: Celebrating Jane Goodall [Trinity University Press]) occasioned by her 80th birthday. And I too have been fortunate that younger writers and artists continue to engage with my work. This week saw the publication of The Art of the Animal: Fourteen Women Artists Explore The Sexual Politics of Meat (Lantern Books).

The crone is part of a mythological trinity of women (the Triune Goddess), reflecting the phases of the moon, that include maiden and then mother (not necessarily literally.)

I had not thought about how this association of the triune feminine figures applied to me until I was in conversation with Jo and Keri about the Unbound project.

Carol Adams in 1975, the year her first article on feminism and vegetarianism was published in The Lesbian Reader. Photo credit: Muriel S. Adams.

I was 23, a maiden, when I realized a connection existed between feminism and vegetarianism, between meat eating and a patriarchal world. By the time that maiden figured out what she wanted to say and how to say it, fifteen years had passed. When I learned my manuscript won a Women’s Studies award and would be published, I was a mother, literally, having just given birth (the baby was with me at the 1990 March on Washington) and I was also a “Mother” metaphorically, I was in the mid-period of life, a generative, creative period, and my book culminated all the theory I had gestated since 1974.

In 2008, Wayne Pacelle, head of the Humane Society of the United States, was featured in the New York Times Magazine.* “‘We aren’t a bunch of little old ladies in tennis shoes,’ Pacelle says, paraphrasing his mentor Cleveland Amory, an animal rights activist. ‘We have cleats on.’” With that quote and that speaker we find manhood asserted for the animal movement in three ways – the speaker, the negation of (aging) women, and the football or sports association of the shoes. It is all structured by representation and a certain kind of voice.

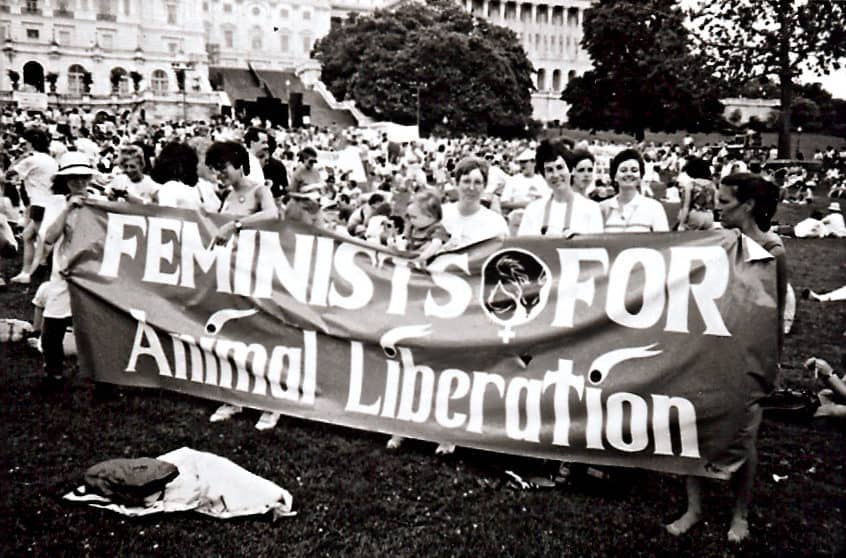

Carol Adams and baby Benjamin at the Washington March for Animals in 1990, with Marti Kheel to her left. If you are in the picture or were at the March, please let us know! Photo credit: Bruce A. Buchanan Now, 25 years after the book was published and 41 years after I first had the idea, here I am, a crone, wiser from those 41 years of living and caring and grieving a world that continues to inflict horrendous suffering on other animals.

The question of “manhood,” enters into the politics of the animal movement at all sorts of levels, and not just in the way the little old lady in tennis shoes is discussed. We could find it in the attempts by philosophers Peter Singer and Tom Regan to articulate theories that reject emotion or sympathy as a legitimate base for the ethical theory about animal treatment. When the working definition of “human” is what manhood is, and rationality is valued as one of the qualities of manhood, then women represent what is not valued—femaleness, and what femaleness is associated with: the body, emotions, and animals. What if part of the resistance to recognizing human exceptionalism (the idea that humans are different from and better than other animals) is the close association between our definitions of humanness and manhood?

Historical memory is fraught and unstable, influenced by stereotypes, including a rigid yet untrue gender binary that privileges men and their words and protects “manhood.” And so, we claim “fathers” but not mothers. The animal activism origin story most frequently told is that Peter Singer is the father of the contemporary movement because of his 1976 book, Animal Liberation. This claim ignores the significant amount of grassroots and analytic work that preceded the appearance of Singer’s book. Well-known animal advocate Kim Stallwood dates the start of the contemporary animal rights movement to Brigid Brophy’s 1965 essay in The Sunday Times, “The Rights of Animals.” I would put its beginning the year before with the publication of Ruth Harrison’s Animal Machines.

Either way, it is a decade before the publication of Animal Liberation. By dating the modern animal movement from Singer’s book, women (Harrison and Brophy among others) are lost to view. In addition, the early feminist concern for other animals that can be found in writings from 1972-1975 is overlooked.

If we trace the animal liberation movement only as far back as Singer’s book, what is lost is not just the women’s voices but the role of feminism and specifically ecofeminism in creating intersectional theory that recognizes connections among oppression. (Lori Gruen and I provide an alternative history in the chapter “Groundwork” in Ecofeminism: Feminist Intersections with Other Animals and the Earth.)

What happens when a group who is supposed to be invisible tries to make animal issues visible? What happens when little old ladies work to give conceptual place to animals? What if around the world, we found women activists simultaneously destabilizing the notion of “manhood” and the usability of other animals? What if we asked them their stories? Maybe the idea of the Triune Goddess and her different phases, maiden, mother, and crone, would apply, or maybe there are multiple models for us to draw upon.

* Maggie Jones, “The Barnyard Strategist” The New York Times Magazine, October 24, 2008. Image Credit: Vance Lehmkuhl

When I started being an activist for animals, I wasn’t a little old lady. But, each year I get closer to being one. (And when someone offers to carry my vegan groceries to my car I wonder if I have arrived at that point). Why has the movement been so anxious to supersede little old ladies? When no one else cared, I can tell you, the little old ladies cared.

We know that the British antivivisection movement of the nineteenth century would have collapsed without women. Women still constitute the majority of animal rights activists. You start working when you are in your late teens or twenties and, before you know it someone is carrying your groceries for you.

It would be nice not to be a little old lady working for the animals but that’s out of my hands. Let’s lace up those tennis shoes and keep moving!

Carol J. Adams is an activist and author of The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory which will appear in a twenty-fifth anniversary edition this October. Her many other books continue her exploration of the intertwined nature of feminist and animal issues. www.caroljadams.com