“For cruelty always disgraces wisdom, power, and progress, and always will.”

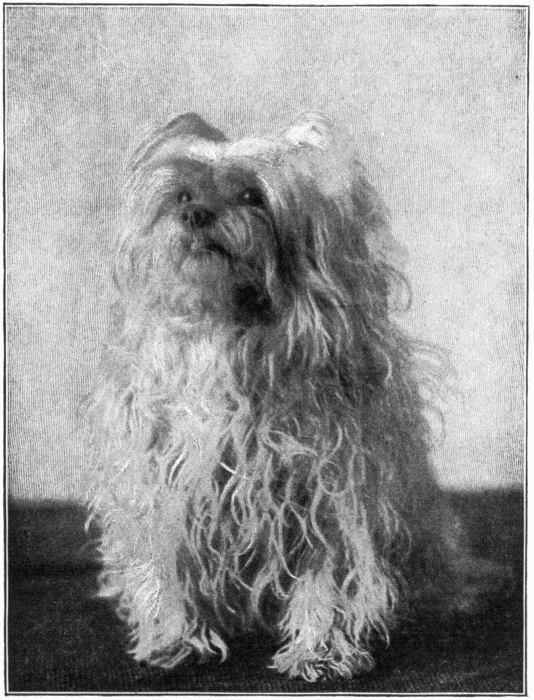

The image of Phelp’s dog that she used as the frontispiece of her 1899 novel Loveliness

O ver a century before videos and social media sites shared stories of rescued laboratory dogs feeling grass and human love for the first time, one author used the power of narrative to evoke empathy for laboratory dogs and spread the message of the anti-vivisection movement. Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’s harrowing anti-vivisection fiction tells stories of beloved animals who are stolen from their human companions and imprisoned in laboratory cages. The celebrated American author was ahead of her time in depicting animal characters with distinct identities and the capacity to love, mourn, and communicate with their human companions.

Decades before she turned her pen to the cause of the anti-vivisection movement, Phelps’s career was launched in 1868 with her best-selling novel, The Gates Ajar, in which she offered post-Civil War American readers a comforting vision of a heaven where they would reunite with beloved family members. As a socially conscious author, she challenged traditional gender roles in her writing. Most memorably, the title character of her 1882 novel Doctor Zay is an independent female physician in a male-dominated profession. Nearly a century before feminists of the civil rights era began burning bras, she fought for women’s clothing reform, urging women in an 1874 essay to “burn up the corsets!” In the final decade of her prolific career, she extended her social justice fight to non-human animals, throwing herself into the anti-vivisection campaign. Alarmed to witness how the practice of experimenting on living animals had rapidly become normalized in American society during her lifetime, she considered it the biggest moral crisis of the day.

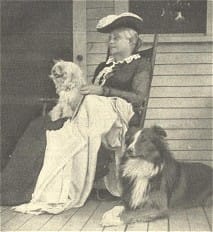

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps with her pets

Like her contemporary Mark Twain, Phelps put her celebrity status as a well-loved author to the service of the anti-vivisection movement. Phelps’s commitment to the movement, though, far surpassed Twain’s, or any other American author of her day. Even while debilitating headaches and declining health increasingly confined to her home, from about 1899 until her death in 1911, Phelps worked tirelessly to convince the world of the immorality of vivisection and to promote compassion for animals. During this time, she wrote three impassioned speeches to the Massachusetts Legislature in support of anti-vivisection bills; several works of anti-vivisection fiction, including the novella Loveliness (1899), two novels, Trixy (1904) and Though Life us Do Part (1909), and at least two short stories; along with several pamphlets, essays, and articles that appeared in national periodicals. She corresponded with lawmakers and elected officials, including President Roosevelt, to solicit support for laws that would restrict the practice of experimentation on animals. Anti-vivisection organizations counted on her as a celebrity spokesperson for the cause.

No one who knows what goes on in our medical schools, our physiological laboratories, our schools of technology and some of our public schools can pass certain buildings in our large towns without a shudder. No prison, no hospital, no criminal court can cause the counterpart to that sick horror.

Excerpt from Spirits in Prison, by Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, 1900*

Phelps’s anti-vivisection reputation was so well established by 1908 that the New York Times quoted her in opposition to the favorite target of the American anti-vivisection movement at that time, John D. Rockefeller, under the headline “DIFFERS WITH ROCKEFELLER, Mrs. [Elizabeth Stuart Phelps] Ward Says There Is No Justification For Vivisection Torture.” Phelps roundly opposed Rockefeller’s defense of vivisection, attacking the popular position that gains in scientific knowledge justified the use of animals in experiments: “Ten thousand things learned, if this were possible, from vivisection, would not justify the intolerable and unpardonable torture to which animals have been subjected by this brutal practice.”**

In her anti-vivisection fiction, rather than anthropomorphizing dog characters by telling the stories from their perspectives, Phelps focuses instead on the nuances of the fictional dogs’ personalities and of their dynamics with humans. Title characters like the poodle Trixy, described as “something of an elf, and loved moodily, and at times, the lad (her human companion) thought, mockingly,” have such distinct identities and vibrant relationships with others that readers may, at times, mistake them for human characters. Phelps was convinced that making the dog characters authentic and relatable would evoke her readers’ empathy for the real dogs strapped to laboratory tables. She was so committed to portraying dogs authentically that she persuaded her publisher, Houghton Mifflin, to use a photograph of her own dog, rather than an illustration, as the frontispiece of her 1899 novella Loveliness, which tells the heartbreaking story of a beloved dog stolen from his invalid child companion and sold to a college laboratory.

There lay the tiny creature, so daintily reared, so passionately beloved; he who had been sheltered in the heart of luxury, like the little daughter of the house herself; he who used never to know a pang that love or luxury could prevent or cure; he who had been the soul of tenderness, and had known only the soul of tenderness. There, stretched, bound, gagged, gasping, doomed to a doom which the readers of this page would forbid this pen to describe, lay the silver Yorkshire, kissing his vivisector’s hand.

Excerpt from Loveliness, by Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, 1899.***

In her careful attention to dogs’ character traits and life stories as a key to making people empathize with them, Phelps was ahead of her time. Long before hashtags, online profiles, and digital photos would facilitate identity campaigns on behalf of animals, this remarkable author put her literary fame and prolific writing to the service of the movement to end the suffering of laboratory animals.

Title quote: Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, “Spirits in Prison,” Independent 52 (22 March, 1900): 695-697.

*Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, “Spirits in Prison,” Independent 52 (22 March, 1900): 695-697.

**New York Times, 29 Nov. 1908, 1.

*** Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, Loveliness. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co, 1899.

_____________________________

Emily E. VanDette is Associate Professor of English at the State University of New York at Fredonia, where she sneaks her beagle, Charlie, into office hours, and teaches courses in American literature, women’s writing, and, coming soon, a new general education course about animal literature. She is deeply interested in the transformative power of literature and has spent most of her academic career dedicated to the recovery of socially conscious women authors of the 19th-century. Her current works-in-progress include a monograph, “Voices of the Voiceless: Literary Animal Advocacy, 1866-1918,” as well as a critical edition of Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’s 1904 anti-vivisection novel, Trixy, which has been out of print for over a century. Northwestern University Press released VanDette’s edition of Trixy in October 2019.